Routine maintenance of rails is desirable and in many cases an essential part of limiting the development of significant rail defects. The principal components of rail maintenance are lubrication, which greatly reduces wear, and reprofiling. Reprofiling, which is most commonly undertaken by grinding, is essential to remove existing corrugation. It is also an essential component of current treatments of RCF. Asymmetric reprofiling helps vehicles steer through curves, thereby reducing all types of defects that occur in curves, while establishment of a more appropriate profile in straight track can reduce hunting.

Hard rails offer a potential treatment for most rail defects, except thermal damage. However, hard rails should only be used if the profile is both appropriate and also routinely maintained: soft rails are more “forgiving” than hard rails.

Maintenance activities occasionally leave features that are both undesirable and avoidable. It is important to recognise features that are inevitable and those that can be avoided.

In this section:

Rail grinding issues

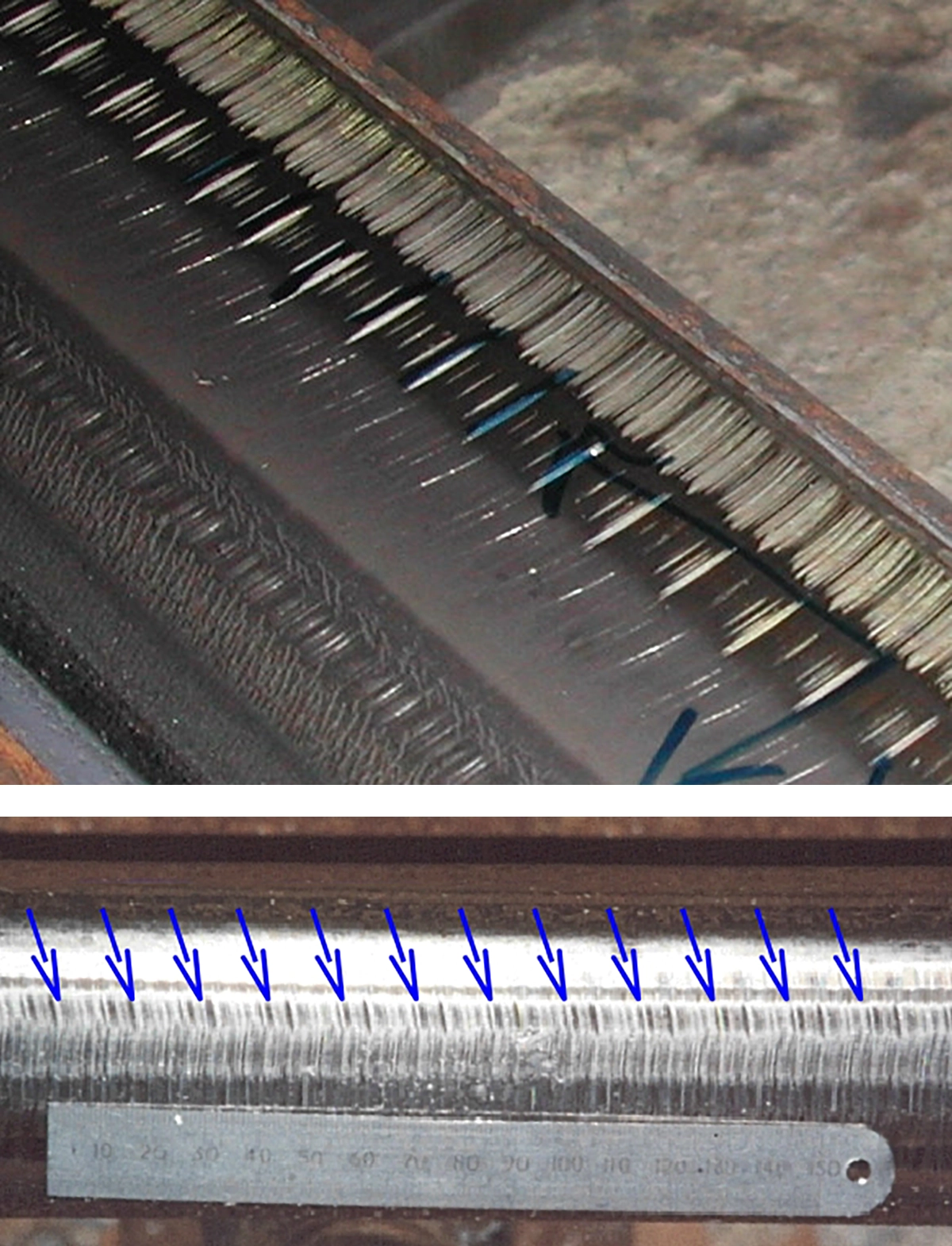

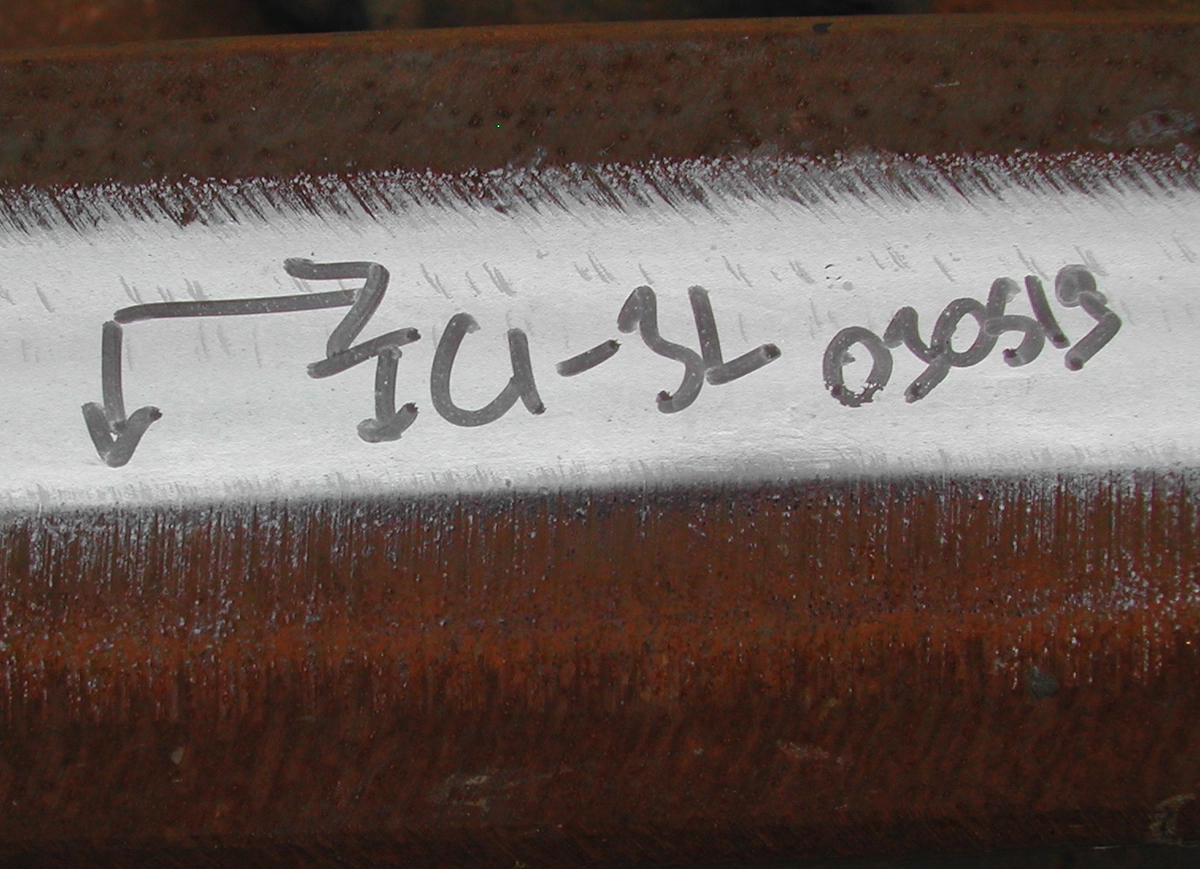

Conventional rail grinding is undertaken with motors that rotate about an axis normal to the rail, typically at 50Hz. For a typical grinding speed of 5-8km/h, this gives a periodic grinding signature at 25-40mm wavelength. Severe grinding, large stone grits and grinding “chatter” can give a pronounced signature, such as that shown. Traffic may cause a characteristic “whistle” until scratches wear away.

Coincidence of the grinding signature with corrugation wavelengths should be avoided as corrugation otherwise returns quickly.

Extreme cases of deep residual grinding scratches, hard rail and low contact stress can initiate surface spalling. This is undesirable and avoidable.

Other grinding techniques can give lower longitudinal roughness but are less able to modify the rail’s transverse profile.

Rail planing issues

Rails are planed in order to remove a significant depth of damaged material (typically >1mm) or deliberately to change the rail’s transverse profile. Discontinuities in profile that give rise to high contact stresses can be created more easily than with grinding, because of the greater depth of metal removal.

This is the case here, where a central plateau with abrupt edges has resulted from planing. The characteristic coils of swarf that result from this operation sometimes lie alongside the rail.

Rail milling issues

When a rail is milled, the milling cutters have been pre-set to establish a specified transverse profile. It is therefore both more difficult than with other reprofiling techniques to vary the profile and also more difficult to establish an “incorrect” profile, unless the specified profile is itself incorrect. Individual milling cutters create a characteristic finish of small, uniform irregularities which wear out under traffic. In extremely noise-sensitive locations these are sometimes removed with longitudinal “shuffle-block” grinding. Small chips of swarf result from milling.

Friction enhancement

Sand is often injected into the wheel/rail contact to reduce wheelslip. During autumn in temperate countries (the “leaf fall” season) a fluid containing abrasive particles is sometimes used to enhance adhesion. Sand or other abrasive particles cause small pits. These pits are a common feature of tram systems, where sand is widely used.